Interview by the fire with Benoît Noël, Writer.

By Marc Thuillier on February 1, 2013 for absinthes.com website. Translation by Artemis, thanks to him.

What triggered your passion for the absinthe history, given that at the beginning you were versed in art history?

In fact, it happened the other way around. I fell into the absinthe kettle as a teenager due to Serge Gainsbourg, whom I consider to be the Paul Verlaine of the 20th Century. I like all types of women from Romy Schneider to Jane Birkin, but I have more success with androgynous women, so I had a soft spot for the Marilou in the song l’Homme à Tête de Chou. She was the woman Baschung dreamed of before the fact: “But her absinthe irises / By her gestures are tinged / With subjacent ecstasies” … It’s the sort of words that speak to an adolescent, no?

I also loved Bordel à Cul by Jean-Roger Caussimon, the singer from the cabaret Lapin Agile: “Bordel à Cul on a pushcart / Verlaine at least had absinthe / Which we banned in 1914 / From which he drew soft moans / And 100-carat rhymes / Sacred brothel of the pregnant virgin / They sell me fake mascara”; or the Jaurès of Jacques Brel: “They were used up in fifteen years, / They finished where they started, / All twelve months were named December / What life did our grandparents have / Between absinthe and High Mass?” Much later, already an absinthe historian, I grasped that these three song excerpts aimed absolutely at the Green Fairy, her power of inspiration or the fact that the freewheeling industrial development of the 19th Century drove numerous uprooted country people to the cabarets in the urban areas.

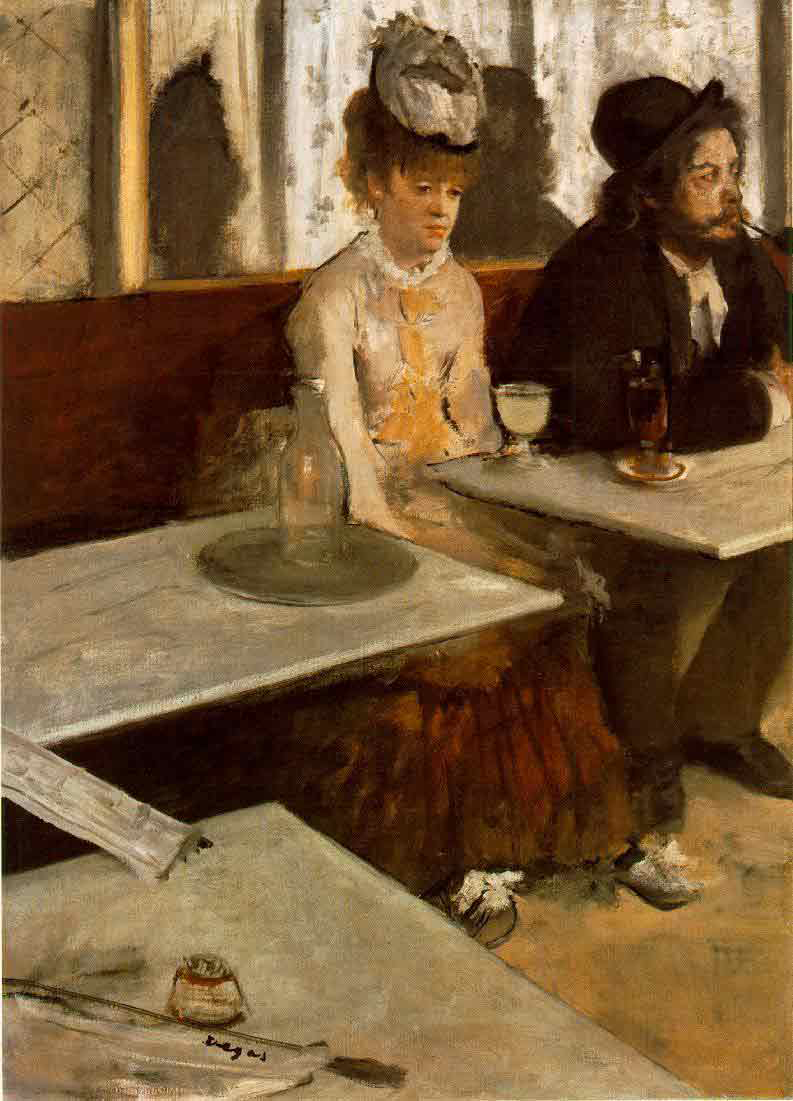

At the same time, our literature text in secondary school, the famous Lagarde & Michard planted absinthe even deeper by drawing a parallel between the Assommoir of Émile Zola and the Absinthe of Edgar Degas, which date from the same year, 1876. It intrigued me …

A couple of years later, at the Sorbonne, Professor Philippe Dagen subtly explained to us how Pablo Picasso and his group of friends had used the anti-absinthism posters to denigrate his rival Henry Matisse and to finally strip him of his status as the leader of the avant-garde. Since the Salon des Fauves (1905), Matisse and friends had revolutionized the use of color, thenceforth used as pure as fireworks. André Salmon and Max Jacob turned the saying “absinthe drives you crazy”, into “Matisse drives you crazy”; his colors are those of an epileptic on the posters slapped up around Montmartre. Then, Picasso was decreed the master of the form and became the Cubist strategist who buried adherents of Fauvism in debates. This bad quarrel could only affect me because then I was writing my thesis on the history of color processes in cinema, of which the ideological conflict between Technicolor and Agfacolor remains the most flamboyant memory …

Some research seems to show that the first Swiss absinthes were made in part of varieties of genepi, which would later be replaced with grand wormwood due to the lack of sufficient genepi for mass production. What do you think?

No, I live in Calvados, Normandy, but regularly go on vacation in Corsica. From Bastia to Boniface, you find wild Artemisia maritima, the color of ashes, mixed with rosemary and described by Alphonse Daudet in his novel Le Phare des Sanguinaires – des Lettres de Mon Moulin. The heart of its distillation by shepherds is a shimmering flavor, a sort of walnut sliding to green grape. In Bordeaux, Nantes as in Charente-Maritime, grows a lighter-colored Artemisia maritima which residents of the West have for a long time transformed into an “Absinthe blanche” without adding color from any other plant. In the Lure Mountains, in Haute-Provence, Artemisia noirâtre is the opposite and so dark that they call it “the black essence”. The shepherds distilled it with fennel and angelica in a grape marc long before and after 1915. The historian Jean-Yves Royer says in Un Alambic au Pied de la Montagne that in Occitan the word “incense” means at the same time the gift of the Magi and wormwood, and the poet Frederick Mistral made no distinction between Artemisia (armoise) and the wormwood of Saint Joan which the young women form into crowns for the Summer Solstice in Europe or the Salt Festivals in New Mexico. In 1936, Albert Camus was struck breathless at Tipasa, in Algeria, by the woolly grey fields of Artemisia judaica. And, in 1864, Louis Favre wrote of the “bluish harvest” of the fields of wormwood in the Val-de-Travers, from which the name “Bleue” comes. There are therefore different wormwood plants that find their way into different recipes according to the region, and Artemisia glacialis or mutellina are only some of the examples, even if youngsters in vacation spots keep stealing vials of genepi more than anything else from the ski resort shops, for lack of absinthe. I know because I did it myself with friends.

To return to the teachings of scientific history, we have established, principally, the immemorial use of Artemisia absinthium to flavor and ward off for a while the souring of wines, hippocras and beers, and from the Romans to the England of William Shakespeare, not forgetting the Gallic beers made of barley, wheat and rye. I am personally astounded by analogies among the old French words “vaissel” meaning a cup (the Grail?), “vaisseau” (ship) or “barrique” (barrel – of alcohol) – “aisens” (absinthe) – “encens” (incense) – and “eisel” (vinegar)! Here are elements that establish the forever-green myth of absinthe of which genepi or pastis will forever remain noble vassals …

Trick Question: Did Doctor Ordinaire have any connection with the origins of absinthe?

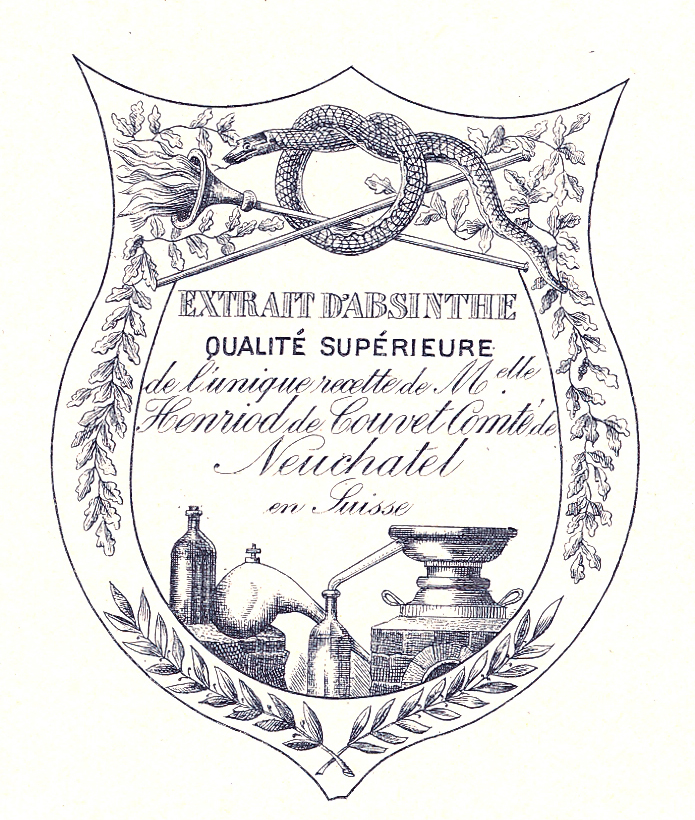

Basically, no; “some connection”, yes. Let’s remember what constitutes in my opinion the “origins” of absinthe. Four primary elements: the appearance of a new anisette with a bitter finish, the change of a curative extract of wormwood into an aperitif drink, the evolution of a drug-infused product into one made by maceration followed by distillation and the establishment of a Swiss basic recipe consisting of anise, fennel and grand wormwood, hyssop, melissa and petite wormwood. It was the work of Suzanne-Marguerite Henriod and of her daughters. Period!

Now, the only description which we have for the panacea of Doctor Ordinaire is that of Edmund Quartier-La-Tente who believed he could assert in 1893 that “the remedy of Doctor Ordinaire was a depurative based upon chicory of the same color as wormwood”. I undertook the critical study of this passage notably by pointing out that “chicory” is hardly a plant used in Switzerland, to treat digestive atonia …

I underlined moreover that this “chicory” could also have a small taste of Franco-Swiss score-settling since after the continental blockade imposed in 1806 by Napoleon upon English merchant ships, the Swiss like the French had to replace coffee with the ersatz of chicory …

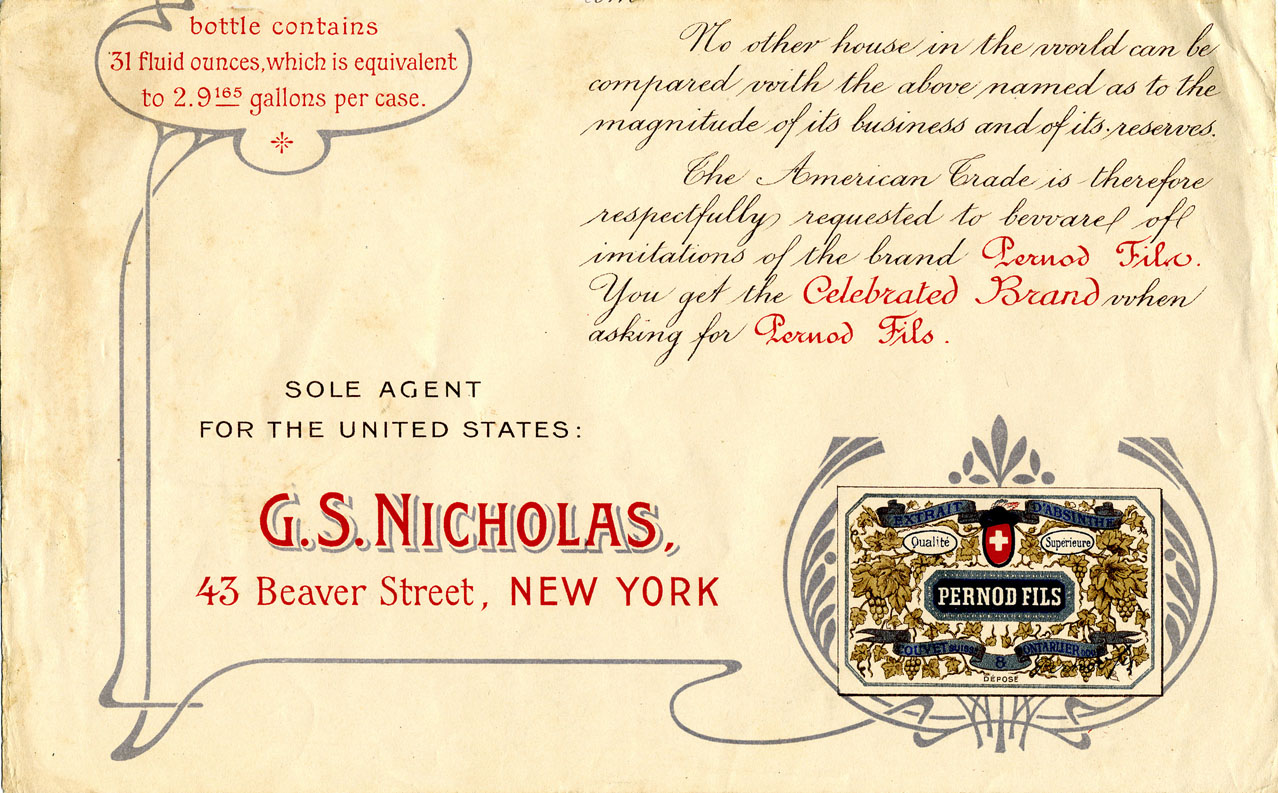

That being said, it is necessary to accept that Doctor Ordinaire was for a long time the close friend and then the next door neighbor of the Henriod family and that they could have worked together on the tentative and progressive elaboration of this drink of thunder! Couvet is a village where notables met daily. It is therefore ridiculous that so-called Swiss historians flog this poor Ordinaire-of-all-evils: charlatan, thief or having only one friend in Couvet, an alcoholic Frenchman, etc. Pierre Ordinaire beyond doubt had the merit of making a quality medicinal extract of wormwood and restoring the honor of the numerous medicinal properties of Artemisia. That’s why we are definitely, as I have always written, in the presence of “four aces”, indispensable at the origins of absinthe: Ordinaire, Henriod, Dubied and Pernod. Of these four people, first place goes to the sole woman even if, in her case, the key element in her favor is the famous label in the Museum of Neuchâtel, which is certainly not as old as the excellent Edmund Couleru claimed.

How do you see the future and the popularization of absinthe in France in the coming years in view of the recent changes to the laws, and is the Pernod group going to have a big role in this popularization seeing that they seem to be ready to invest in a distillery to produce a distilled absinthe?

I am skeptical about a revival of absinthe on a nationwide scale. To this point, Pernod-Cusenier has tested two tiny productions of absinthe substitutes (Oxygénée in 2001 and Pernod in 2003) but they were looking long term, and at exportation, which they cannot do without, more so than at the French market. And, to develop an international market for absinthe is difficult. Today Whisky easily dominates the spirit market (40%) along with vodka (14%) and rum (11 %). The anise spirits account for only 6% and in this small segment, absinthe amounts to almost nothing even if its sales are in well-known increase from almost zero.

A total change of mentalities and tastes would be needed. How many macho men accept only whisky for fear of rocking the boat? What part of the worldwide population appreciates anise except the Mediterranean coast which already has its traditional alcohols in this domain, and Germany or the Netherlands, via cumin or caraway? It was necessary to wait for No. 45 of Whisky and Fine Spirits Review to find a lead article on absinthe. Before last Christmas, the newspaper Le Monde titled one of its supplements: “Wines and Spirits” but I searched it in vain, not the slightest trace of spirits. If only absinthe had, like cognac, the favor of the rappers who restored to fashion a spirit in decline but conserved nevertheless the brand image of an alcohol honoring the signature of commercial contracts. Absinthe is short of publicity engines and as far as I know Johnny Depp and Marilyn Manson have never set foot in Pontarlier. At the end of 1960s, the Champagne firm Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin, then the Martini-Baccardi and Pernod Ricard groups bought some small Norman outfits producing Calvados but they quit the race after only one lap, for lack of sufficient profitable volume.

The commercialization on a large scale of absinthe remains handicapped by its nature, its myth, its ritual and its alcohol content. To boost the spirits market, cocktails are in vogue, but absinthe is a cocktail in itself, a delicate cocktail of plants and spices. It thus doesn’t fit in except for classics as our research in mixocology showed in Forcalquier in May, 2009: Absinthe Mojito, Death in the Afternoon, Gold Sands or Suissesse. If absinthe loses its status as “the drink you love to hate” its aura is also broken. Its fascinating drinking rituals hinder its expansion because of their complexity and there are too many “purists” who systematically mock any evolution such as the recent Pernod fountain. Finally, leading chefs prohibit drinks stronger than 45° for fear of rendering the palates of their customers incapable of perceiving their talents. Far be it from me to discourage the Pernod group from investing in a distillery but their leaders know that the first attempts of Pernod International to reintroduce an absinthe spoon in the U.S. for use with Pernod Fils Pastis go back to 1993!

We can count several hundred absinthes on the European market; do you think that a European definition of absinthe is going to reduce this number to only quality absinthes and to polish the sulphurous past (and present) image of the drink?

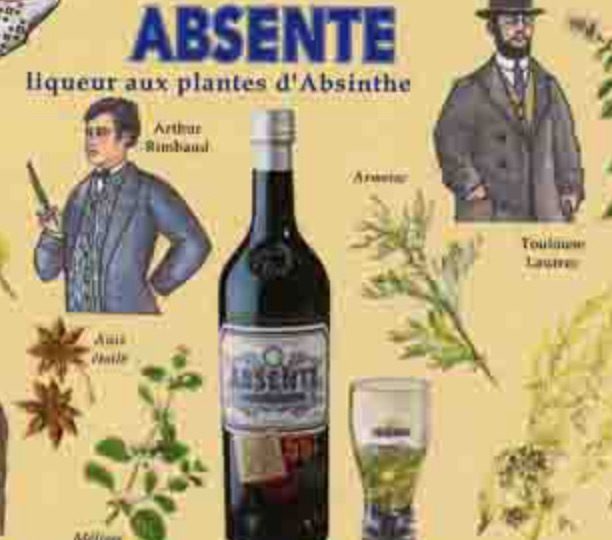

It’s obvious that the absinthe market is encumbered by the 90% of pathetic fluorescent glacial fluids but we should not forget that this is the ransom of the oversized myth of absinthe. This oversized myth holds principally in the way that young people full of artistic ambition want to think that a psychotropic substance can lead them to genius, glory and money without having to tirelessly exercise their prospective talents. It is the unfounded perception or if you prefer one of the most common hallucinations to the world! And, it happens that absinthe is seen as the martingale of 19th century artists for the simple reason that, as I have killed myself explaining, “the applicant to the green fairy” disdains to live his dream. To wit, the plant Artemisia absinthium of which the drink is a product, has since time immemorial been mixed with hellebore seeds, the only drug capable of restoring the intestinal flora to the stomachs of painters eaten up by lead or the ceruse in pigments, and subsequently restoring to them the exuberance to create. It is therefore natural that the prestige of Artemisia absinthium has been transferred to the exceptional aperitif rightly considered to be the magical potion of the artists!

I am resolutely ecological and persuaded that medicine will before long be forced to admit publicly all that it still owes to plants. Let us take for example another key plant of the apothecary-herbalists, St. John’s Wort. Its Greek name is Hypereikôn, which means “above the icon”. The Ancients put bouquets of it above their pious images. This means that, far from being crazy, they bet just as much upon the spirit as upon the body, which intellectuals wrongly set apart. If their prayers were not answered, at least this powerful antidepressant, still sneakily used by the modern laboratories, regulated their moods, sleep and melancholia. It is therefore necessary for us to return as a matter of urgency to fundamentals and to honest absinthes, all the more so as Artemisia means “integrity”. My guests are always surprised by the potency of a simple infusion of oregano, melissa, rosemary, or even sage, some sprigs of which I picked from the garden a few minutes before. It is therefore necessary for us to return to fundamentals, and that’s why I wrote that the Absinthe Sauvage from Émile Pernot was a success. Man is a fund of energy and this one lifts gives you a lift with a shiver and a burst of energy; fruity and raw like coriander. Now, it is necessary to be wary of fashions and notably those launched on the Internet. Ten years ago everyone swore only by the mythical “Bleue” of the Val-de-Travers that the whole valley provided while laughing up their sleeves. Today, we’re less excited by insane thujone levels but swear by vertes in which fennel stifles the freshness of the green anise …

In second analysis, even if I am a priori recalcitrant to an excess of standards, to avoid falling into the flaccid consensus of a flavorless product and because every distiller should be able to keep his secret weapon like Lagardère, I recognize that Europe by aligning itself with OMS recommendations. made possible the recent legalization and pushed the last recusant country (France) to fall in line with the majority. Therefore if the AOC or IGP turn out to be insufficient, why not European terms and conditions?

Do you think that a new ban on absinthe could happen if it continues to be consumed on fire or by the shot glass by young people? Shortly after the re-legalization of absinthe in the USA, the press featured two fatal accidents following excessive consumption of absinthe reminiscent of the Lanfray affair where alcohol consumption was more the issue than the consumption of absinthe itself.

Consumption of flaming absinthe is another avatar of the oversized myth. At the time of historical absinthe, never was it consumed on fire; that constitutes a heresy besides because it makes absinthe lose aroma and flavor. All there was at the time was the Cafe Gloria or coffee with brandy with which they burned a sugar cube using a small spoon or notched grille. I therefore discourage my interlocutors when they ask if this style of consumption is desirable. Now, I am often surprised to see absinthe “fundamentalists” laying into someone defending this option. As long as there are mistakes the myth is well alive …

Let’s recall that the revival of Czech absinthe that I described in the journal Stupéfiant! in 1999 itself proceeds from a huge mistake. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, young Americans, always intrigued by absinthe, forbidden in their country since the end of prohibition in 1933, clamored to Czech waiters for it, all the more of course because being in Bohemia, it was necessary to taste the renowned drink of bohemian artists. Oh, the faces of the waiters who had never heard of absinthe!

As to the risk of accidents leading to a new ban, I notice that it is more the stone tablets of liberalism than real concern about public health that dictate such law to the legislators, whatever they might pretend to believe on the subject. So, let there be no misunderstanding about it; absinthe was banned in 1915 to please the wine lobby and finally legalized in 2011 to prevent a prospective market from being captured by foreigners …

Last question: have you met the famous Green Fairy? Or more generally: have you yourself felt harmful or beneficial secondary effects from the consumption of absinthe? Some people speak of augmented vision, of mental clarity or else of improvement of the intellect which it could be imagined would have helped the artists and writers of the 19th Century a little. Myth or reality?

A number of scientific studies or philosophical essays on the consumption of psychotropics mention that in the end, love is the best drug of all. Indeed, love lightens your life, makes you forget death for a moment, grafts wings on your back and encourages creation via artistic muses. We see here the first links with the epicurean tasting of absinthe which amounts to learning and knowing personal metabolism and to not exceeding alcohol tolerance. Look at the strange idea of giving the name “Absinthe” to a performance of amazing gymnasts in Las Vegas. Isn’t it because the controlled consumption of absinthe is the promise of the “Seventh Heaven”?

Quality absinthe skillfully combines three paradoxes: it takes control of the tongue without overpowering the palate, it unfolds in the mouth a bouquet of successive flavors that are well-blended together, and tickles without irritating the glottis. Sommeliers have a pretty name for these fireworks – “the peacock’s tail”. In other words, this “grip” precedes the “surprise” and this “peacock’s tail” shines up to a certain “point”, different for each individual.

Absinthe captivates pupils and papillae and, a vasodilator like any alcohol, it surreptitiously transforms you Your blood pressure decreases, your chest inflates, your lungs remember how to breathe, your trachea aerates, your digestive apparatus disencumbers itself, and you … lift your head, reinvigorated. Your ankles leave the floor, and lighter, you grow taller, and in doing so, above the futile fray, you decipher the world in depth with new eyes. You have a hold on the world, a “sur-prise” as the poet Andre Breton loved to say when he superbly proclaimed “Alfred Jarry, surrealist in absinthe”. That is what you may well call “augmented vision”.

Parallel with the broadening of horizons, the ritualized mode of consumption of absinthe involves an authentic dilation of time. “Make the good times frothy” was once aptly suggested as a slogan for beer. What could be better than the black ball which should have squashed Indiana Jones a long time ago, while the demiurge Steven Spielberg continuously delays the fatal outcome?

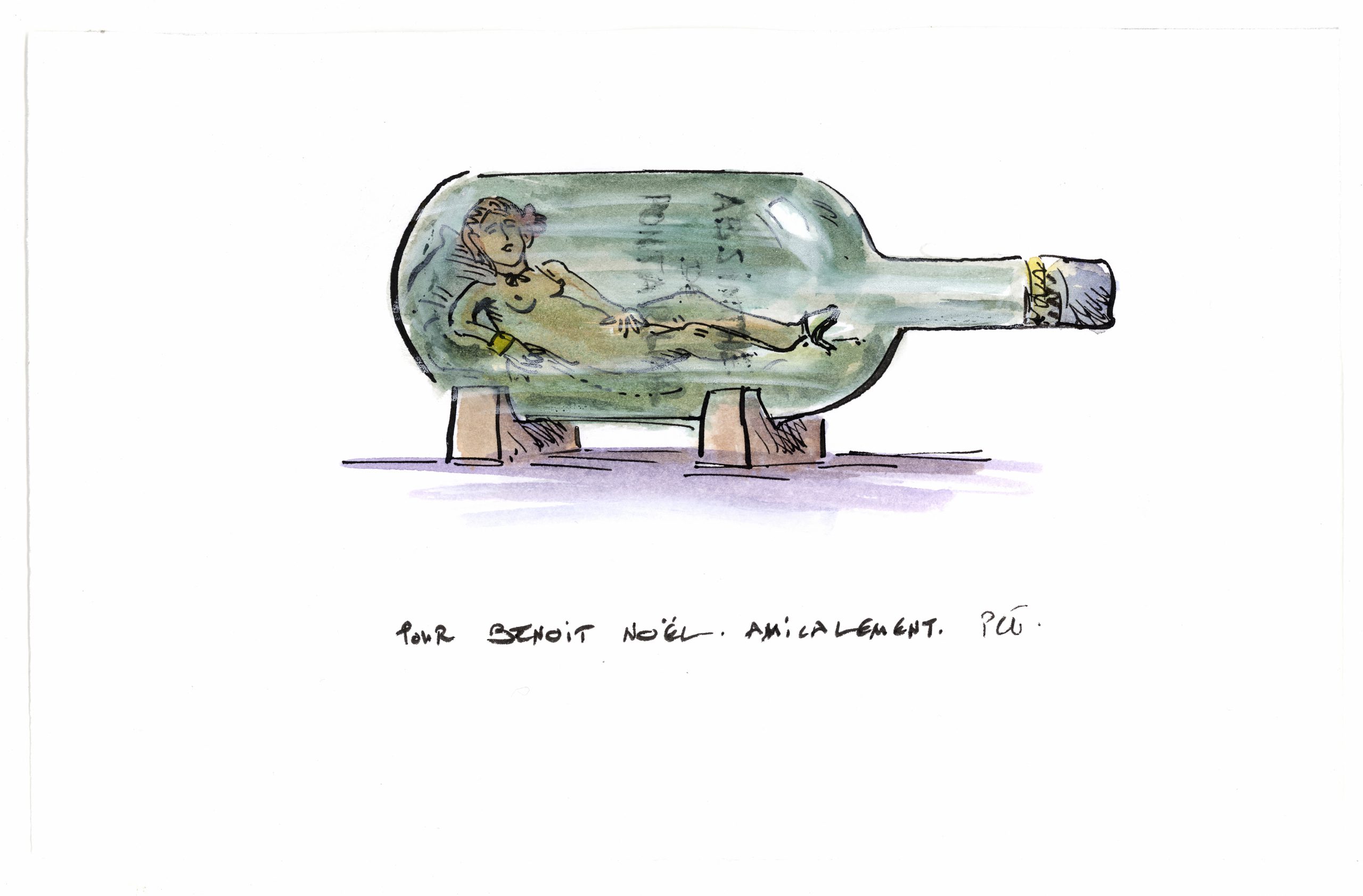

Let’s return to the magus Gainsbourg and his Amour de Feintes, a track completely summing up the subtle and wicked game of seduction: “Absinthe color / Smell of time / Never shall be / As before”… These are surely not verses born of absinthe drunkenness but debts owed to a nostalgia for good fairies. It is certain that everyone finds in absinthe more or less what he seeks, as I pointed out earlier, regarding the collective hallucination of a martingale for genius. I also itemized my stand in the forum of the Virtual Absinthe Museum: The supposed hallucinations on absinthe or the multiplication of little Salvador Dalis … the unhappy story of a man who suddenly airs his dirty laundry in public, what you call a “harmful secondary effect”. That’s why, without disclaiming a placebo effect for absinthe, it should not be boiled down to this! It is not for nothing that Ernest Hemingway evoked “a truth serum with the flavor of wormwood” while pretending that the second glass erases the “remorse” of having spoken too quickly.

Finally, Marguerite Duras maintains justifiably that: “The true subject of writing is writing” and we may extend that to “the true subject of absinthe is absinthe”. Never has a drink provoked so many works capable of spreading its myth so continuously but first of all, never has a drink seemed to be such a key in the investigation of the real.

Let’s take the concrete example of the famous tableaux of Edgar Degas, previously mentioned, that only the clemency of absinthe and its scientific study have allowed me to perceive and then to see for real. As I explained in L’Absinthe, Muse de Peintres (1999), the three heavy marble tables do not have cast iron legs and seem to levitate like the cafe amazon and her companions, two zombies whose shadows in the mirror of the Nouvelle-Athènes cafe seem to come from beyond the grave. By any logic, these tables should crash to the ground and explode the picture frame. In the foreground the painter placed two newspapers to either side of a pyrogène and we sense there is bad news in the place from where they come.

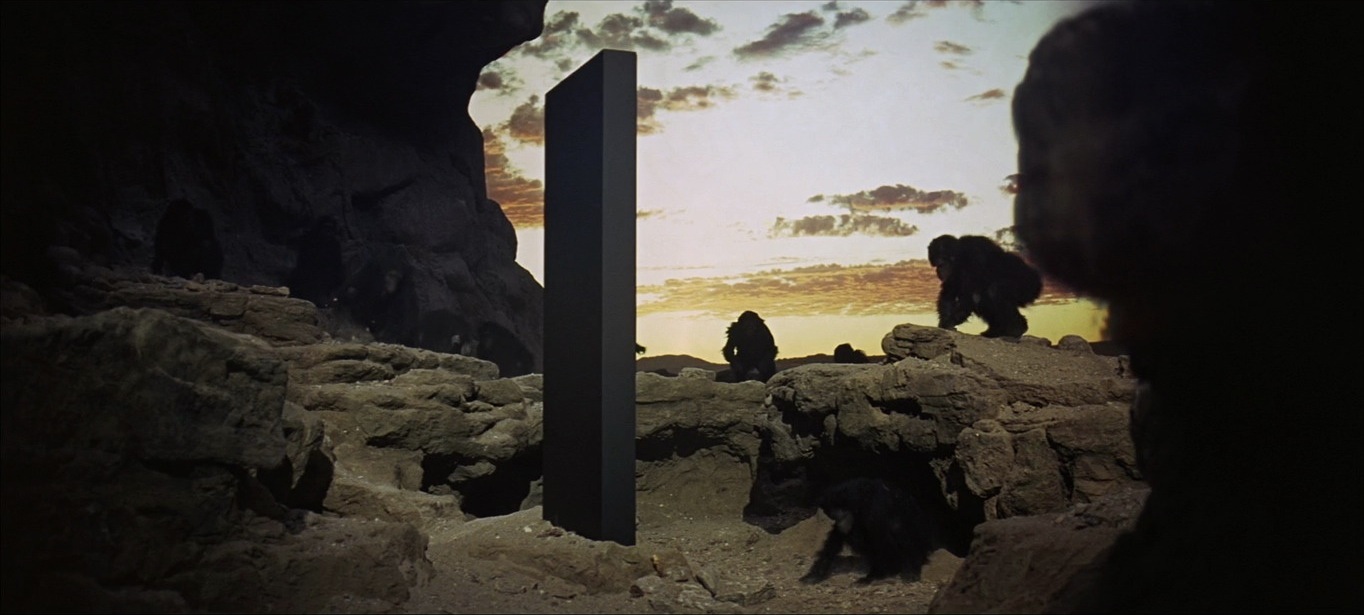

Then, there came a day when I saw the correlation or rather the absolute correspondence of these tables with the mysterious black monolith which opens and closes 2001 – A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick (1968). Degas had found a way to suggest the doors that absinthe opens to the world and the other side of world; S. Kubrick was suggesting that other worlds are at our door!

Ah, yet another detail. Degas’ model for this painting, Ellen Andrée recounted that the facetious painter who was already painting “the things behind things” had represented the “world upside down” because in real life, she didn’t touch absinthe while Marcellin Desboutin, here shown with a cup of coffee, abused it. It gets worse: Degas terribly uglified the sublime Ellen Andrée, whose bright beauty Edward Manet and Henry Gervex restored for us in La Parisienne or Rolla. My subjugation of absinthe allows me then to set the world right side up …

(Interview by Marc Thuillier for Absinthes.com. Translation by Artemis & Marc Thuillier)

Comment by Alan – February 3, 2013 – 7:01 pm

Excellent interview!

Comment by S.B. MacDonald – February 4, 2013 – 5:16 pm

This is perhaps the best, most informative article/interview I’ve seen on this subject. Thanks for this!

Comment by Damir Tomicic – February 5, 2013 – 9:45 am

Great interview! Benoit’s a truly expert and a valuable source of information. I always enjoyed reading his books, most preferable with the glass of Absinthe in the evening. Certainly the best you can get on the market focused on this topic.

Comment by Ken Tatham – February 5, 2013 – 4:23 pm

I didn’t know much about the subject before reading the article. Highly entertaining. Thanks

Comment by Marc Bernhard – February 5, 2013 – 6:35 pm

Excellent and informative. This article is indeed worthy to be saved and re-read.

Comment by Martin Zufanek – February 5, 2013 – 9:03 pm

Excellent article! One of the best I’ve ever read about the subject. Thank you.

Comment by Markus Lion – February 6, 2013 – 11:59 am

Very good interview/article. I really enjoyed the reading!

Pingback by Rosemary benoit | Greenlivingand – February 7, 2013 – 6:02 pm

[…] Interview by the fire with Benoît Noël, writer. – TheMAG Absinthes.com […]

Comment by Christian Jaberg – February 8, 2013 – 2:30 pm

Dear Benoît Noël

Comprehensive and inviting, as f.e. Absinthe -a Myth AlwaysGreen, too.

And the best to me – and again – a lot of home work – to retrace, grow rich and fond.

After a month of fasting I will have a Calvados on that!

Many Thanks for sharing.

Best, Christian